White-nose syndrome is a disease affecting hibernating bats. Named for the white fungus that appears on the muzzle and other parts of hibernating bats, WNS is associated with extensive mortality of bats in eastern North America. First documented in New York in the winter of 2006-2007, WNS has spread rapidly across the eastern United States and Canada, and the fungus that causes WNS has been detected as far south as Mississippi and as far west as the state of Washington.

Bats with WNS act strangely during cold winter months, including flying outside in the day and clustering near the entrances of hibernacula (caves and mines where bats hibernate). Bats have been found sick and dying in unprecedented numbers in and around caves and mines. WNS has killed more than 5.7 million bats in eastern North America. In some hibernacula, 90 to 100 percent of bats have died.

Many laboratories and state and federal biologists are investigating the cause of the bat deaths. A fungus discovered in 2008, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, or pd, (formerly Geomyces destructans), has been demonstrated to cause WNS. Scientists are investigating the dynamics of fungal infection and transmission and searching for a way to control it

Download a from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Please note: due to the volume of changes to a number of states, provinces, and species affected after the 2017/2018 survey season, those figures on the fact sheet have not been updated. See ” and “ ” on this web page for the most current information.

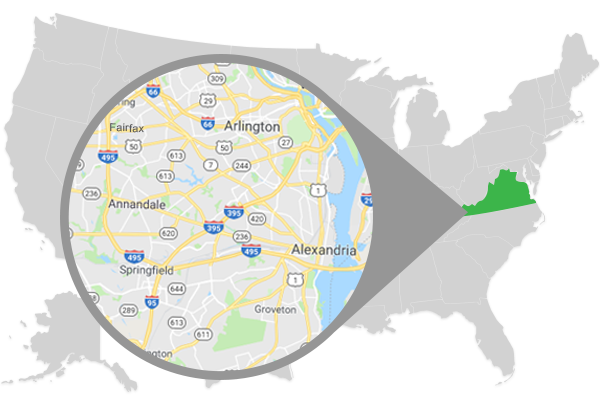

Where has WNS been observed

White-nose syndrome has been confirmed in bat hibernation sites in 32 states and 7 Canadian provinces: Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island and Quebec

In addition, the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, has been found in four additional states: Mississippi, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming.

How is WNS transmitted?

Scientists believe that white-nose syndrome is transmitted primarily from bat to bat. There is a strong possibility that it may also be transmitted by humans inadvertently carrying the fungus from cave to cave on their clothing and gear.

Is global climate change a possible cause of WNS?

While many possible causes of white-nose syndrome are being studied, no credible evidence links climate change and WNS. Weather conditions in caves and mines where bats hibernate were stable during when WNS emerged, and no data show changes in insect prey numbers in affected areas. Potential impacts of global climate change will continue to be monitored as we learn more about the disease.

How does WNS affect bats?

We have seen 90 to 100 percent mortality of bats (mostly little brown bats) at hibernacula in the northeastern United States. However, mortality may differ by site and by species within sites.

The endangered Indiana bat hibernates in many affected sites. We are closely monitoring Indiana bat populations in many hibernacula and, to the extent possible, in their summer maternity colonies. During the winter of 2008-2009, biologists conducted the biennial rangewide winter counts of Indiana bats. Population estimates based on this count show the overall Indiana bat population declined by approximately 17 percent. This is the first observed decline since 2001.

In addition to the Indiana bat, white-nose syndrome has reached the ranges of three more endangered bats: gray bats, Virginia big-eared bats and Ozark big-eared bats. The Northern long-eared bay was listed as threatened in 2015, the first bat species to be listed due to the effects of white-nose syndrome. We are closely monitoring these species as WNS continues to spread.

Does WNS pose a risk to human health?

Thousands of people have visited affected caves and mines since white-nose syndrome was first observed, and there have been no reported human illnesses attributed to WNS. We are still learning about WNS, but we know of no risk to humans from contact with WNS-affected bats. However, we urge taking precautions and not exposing yourself to WNS. Biologists and researchers use protective clothing when entering caves or handling bats.

What should cavers know and do?

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the states request that cavers observe all cave closures and advisories, and avoid caves, mines or passages containing hibernating bats to minimize disturbance to them. The Service asks that cavers and cave visitors stay out of all caves in the affected states and adjoining states to help slow the potential spread of white-nose syndrome. Local and national cave groups have also posted information and cave advisories on their websites.

What should you do if you find dead or dying bats, or if you observe bats with signs of White-Nose Syndrome?

- The Center for Disease Control has additional information for .

- Contact your state wildlife agency, file an electronic report in those states that offer this service, e-mail U.S. Fish, and Wildlife Service biologists in your area, or contact your nearest Service field office (find locations at to report your potential WNS observations.

- It is important to determine the species of bat, in case it is a federally protected species. Photograph the potentially affected bats (including close-up shots, if possible) and send the photograph and a report to a state or Service contact (above).

- If you need to dispose of a dead bat found on your property, first BE CERTAIN THE BAT IS DEAD. Use a trowel or other tool to scoop the dead bat into a plastic bag. If you must use your hands, wear a heavy leather glove covered with a plastic bag or disposable glove to pick it up. Place both the bat and the bag or disposable glove into another plastic bag, close the bag securely, spray with disinfectant, and dispose of it with your garbage. Thoroughly wash your hands and any clothing that comes into contact with the bat.

- If you see a band on the wing or a small device with an antenna on the back of a bat (living or dead), contact your state wildlife agency or your nearest Service field office, as these are tools biologists use to identify individual bats.

What are signs of WNS?

Bats may lose their fat reserves, which they need to survive hibernation, long before the winter is over. They often leave their hibernacula during the winter and die. As winter progresses, increasing numbers of dead bats have been found at many affected locations.

White-nose syndrome may be associated with some or all of the following unusual bat behavior:

- White fungus, especially on the bats’ nose, but also on the wings, ears or tail;

- Bats flying outside during the day in temperatures at or below freezing;

- Bats clustered near entrances of hibernacula; and

- Dead or dying bats on the ground or on buildings, trees or other structures.

Hibernating bats may have another white fungus not associated with WNS. If a bat with fungus is not in an affected area and has no other signs of WNS, it may not have WNS.

What are federal and state agencies doing to fight White-Nose Syndrome?

An extensive network of state and federal agencies is working to investigate the cause, source, and spread of bat deaths associated with white-nose syndrome, and to develop management strategies to minimize the impacts of WNS.

The overall WNS investigation has three primary focus areas: research, monitoring/management, and outreach. For example, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is conducting winter surveys to document and track affected sites, working with the caving community and local cave owners to target potential sites for surveys and protective measures, and securing funding to identify and fund research on the spread and management of WNS.

In 2009 and 2010, the Service led a team of federal and state agencies and tribes in preparing a national white-nose syndrome management plan to address the threat to hibernating bats. The plan provides a framework for coordinating and managing the national investigation and response to WNS. The National Plan for the Assisting States, Federal Agencies, and Tribes in Managing White-Nose Syndrome in Bats finalized in May 2011, outlines the actions necessary for state, federal and tribal coordination, and provides an overall strategy for investigating the cause of WNS and finding ways to manage it.

What is the purpose of the national plan?

As WNS spreads, the challenges facing wildlife managers in understanding threats to bat populations and managing WNS continue to increase. Collaboration among state, federal and tribal wildlife management agencies and NGOs is essential to the effectiveness of the collective response and ultimately to the survival of bat species across North America.

The national plan provides a framework for coordinating and managing the national investigation and response to WNS. The plan outlines the actions necessary for the state, federal, and tribal coordination, and provides an overall strategy for investigating the cause of WNS and finding ways to manage it.